We are taught that water is freely diffusable via cell membranes--even in the absence of aquaporin function, there are usually some water molecules which traverse the lipid bilayer. However, there are tissues within the human body which must be extraordinarily tight: two that come to mind are the thick ascending limb of the nephron, as well as the bladder epithelium. How does the epithelium comprising these "water-tight" barriers obtain these characteristics?

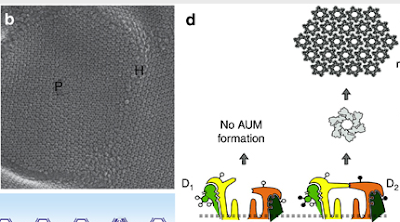

The epithelium lining the bladder (a.k.a. "the urothelium") is one of the tightest epithelia in the body: the bladder must be capable of holding urine for long periods of time without leakage, and furthermore serves as an important barrier for toxic substances filtered by the kidney. The urothelium's water-impermeable properties can be explained in large part by a family of proteins called the uroplakins. The uroplakins form tiny, hexagonal arrays of particles--visualized best by electron microscopy (see figure taken from this excellent recent KI review by Wu et al)--which comprise structures called "urothelial plaques" that overlie the plasma membrane of superficial umbrella cells of the urothelium. It is thought that these plaques are tethered to the lipid bilayer, limiting the movement of phospholipids and therefore limiting water permeability. Interestingly, mice deficient in uroplakins show increased water permeability.

The uroplakins also appear to play a role in urinary tract infections; the uroplakin Ia/Ib glycoprotein is the means by which some strains of E. coli adhere to the urothelium.

No comments:

Post a Comment