I spend a lot of time discussing patients with renal disease and monoclonal gammopathies with my haematology colleagues, trying to figure out what is of ‘renal significance’ and ‘undetermined significance’. One of those discussions recently was around a normally well 70 year old lady. She presented with several pre-renal insults including a febrile illness, relative hypotension and NSAID use for joint pains. Her renal function rapidly deteriorated and she became oligoanuric requiring haemodialysis.

It is not surprising that we pick up a lot of monoclonal gammopathies in patients with deteriorating renal function or proteinuria as MGUS affects 3% of patients over the age of 50. Recent evidence suggests that MGUS progresses to myeloma or other plasma cell or lymphoproliferative disorders in 10% of patients at 10 years, and higher than this in those with an abnormal serum free light chain ratio or IgM paraprotein.

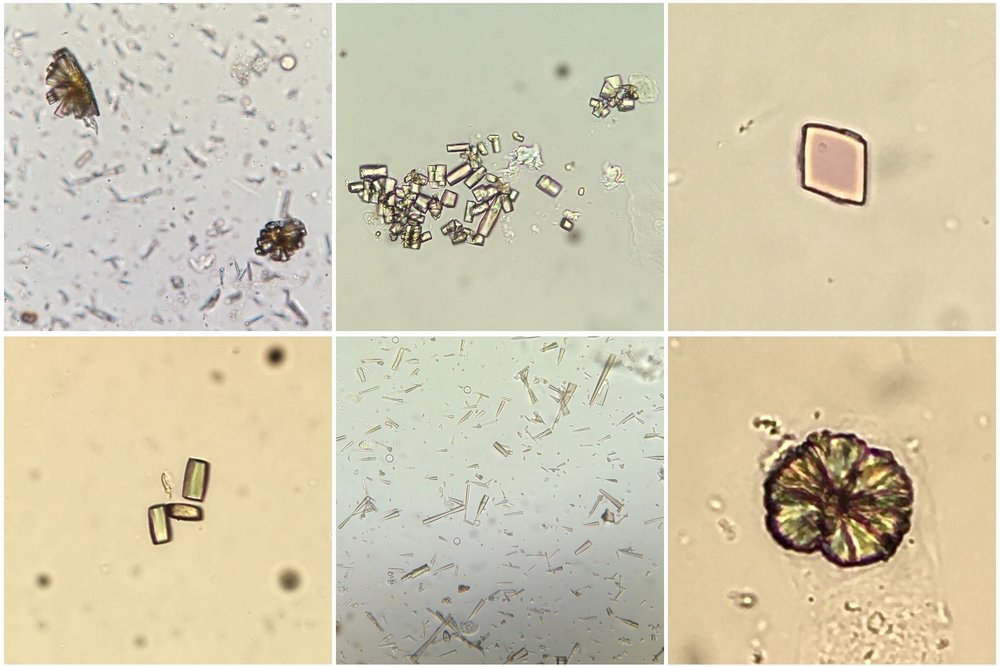

Monoclonal immunoglobulins or immunoglobulin-derived fragments can be deposited in the kidney in a number of patterns (previous RFN post from Nate):

- Crystalline deposits: cast nephropathy in myeloma

- Organised fibrillar deposits: AL amyloidosis (Congo Red stain positive)

- Organised microtubular pattern: immunotactoid GN or type I cryoglobulinaemia. Fibrillary GN is from polyclonal IgG deposition (not usually associated with a paraprotein) and on EM has slightly smaller fibrils (approx. 20nm in diameter) than immuntactoid GN.

- Disorganised granular deposits as in LCDD and HCDD

Immunotactoid GN usually presents in a more insidious pattern with hypertension, haematuria and proteinuria rather than acutely as in this case. The straight, hollow tubules are over 30nm in diameter and are usually composed of crystallised monoclonal IgG. The diagnosis can be missed when EM is not performed. It is usually secondary to lymphoproliferative diseases, typically CLL or B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma but also MGUS. Treatment is based on the underlying disease, and in cases as this vigilance for progression is vital.

Post by Ailish Nimmo